Peter Jeppsen: I travelled to London to celebrate Hitchmas with Lawrence, Stephen, Richard, and Douglas

Following an off the cuff suggestion from me to come to London to get a book signed that he couldn't get signed in Boulder, Peter travelled there, and gives here a personal reminiscence of the event.

Peter Jeppsen had communicated with me on Facebook about my books and appearances, and when I did an event in Boulder, he attended the event, and had hoped that books would be sold there. Alas, none were. When he inquired about my next event I told him I would be speaking in London, and he should come there to get a book signed. I was being facetious, or thought I was, but to my great surprise, Peter contacted some time later to let me know he had purchased tickets to the Merry Hitchmas event. I was please to see him there that evening, and finally sign his book. After the event, Peter reached out to me to say he had written a piece about his experience (see also his substack mkingbyrd.substack.com), and I thought it might be fun for Critical Mass Readers who weren’t there to get a sense of the experience, of at least one person. I offered to publish it here. So, here you go…. Thanks Peter.—LMK

_____________________________________________

Merry Hitchmas!

I traveled to London in December to an event celebrating the legacy of Christopher Hitchens. The event featured Douglas Murray, Richard Dawkins, Stephen Fry, and Lawrence Krauss.

What do you get when you cross the legacy of a vehement anti-theist and despiser of Christmas with an Atheists UK and Origins Project fundraiser? Justification to travel to London for an event known as Merry Hitchmas! A celebration of the life and contributions of the late Christopher Hitchens in London, England at the Royal Geographical Society (RGS). Put on by three organizations: The Origins Project, the How To Academy, and Atheists UK ; with special guests made up of those with whom Hitchens was close in life. The part of emcee was played by theoretical physicist and Origins Project President Lawrence Krauss. He shared the stage with actor/writer/etymologist/British National Treasure, Stephen Fry, evolutionary biologist and fellow four-horseman of the atheist apocalypse Richard Dawkins, and sometimes controversial/always insightful author and journalist Douglas Murray.

How did I end up there? The long answer involves my journey out of Mormonism in which I found Hitchens. The immediate circumstances involve what my Mormon brain would have interpreted as a series of small, divine proddings that started with Lawrence Krauss visiting Boulder, CO to speak with Stephen Hicks. For the preceding six years, I’d hardly opened Facebook. Why I did, I don’t know but an advertisement for the event via Krauss’ page invited me. It almost felt like some higher power were directing me to go listen to Krauss who, once embracing his friend Christopher’s antitheist designation, now called himself an apatheist. Hitchens was the reason I know about Krauss and the reason I went to hear him speak.

A night-of, pre-event pillaging of Boulder bookstores proved fruitless in finding any of Krauss’ published works. I jokingly asked him at the after-event signing if, since he knew how a universe can come from nothing, could he also produce one of his books from nothing for me to purchase, collect an autograph therein, and take home? He couldn’t big-bang a book into existence but did offer this invitation: “Why don’t you come to London and I’ll sign a book there.” The event: the December 14th “Merry Hitchmas.” An outrageous idea on first glance, with time Krauss’s invitation seemed sliver-lined with sincerity if understandably flippant.

I mused for two weeks on making the trip. Convinced by my sister and a friend that to make such a trip was not selfish but self-fulfilling and encouraged by my wife who acknowledged that it seemed important to me, I purchased a ticket to the event before they sold out. It took another two weeks when, circumstances seeming again as if meddled with by some force beyond my comprehension, I was delayed in purchasing an airline ticket by unrelated ill-fortune. The closing door opened a window, as is often said of God’s ways, in that the overnight delay saw a significant price decrease in airfare.

Emcee for the night and personal friend to Christopher, Mr. Lawrence Krauss

L to R: Douglas Murray, Richard Dawkins, Lawrence Krauss, Stephen Fry (photo credit to Mr. Krauss)

Why did I feel compelled to go? I regrettably discovered Christopher Hitchens two years after he’d already passed. It was in discovering Richard Dawkins that I found Christopher and others. From what I’d heard, I feared this may be Dawkins final public appearance. Knowing I’d missed Hitchens in life, I wanted a chance to meet Dawkins. Further motivation came in getting to meet Douglas Murray and Stephen Fry. An event in his honor would bring these influential men together at one venue.

Mr. Richard Dawkins and an annoying American

On the heels of purchasing the plane ticket, I contracted what felt like Covid. A work colleague tested positive the same weekend another colleague and I showed analogous symptoms. I felt fortunate. I wouldn’t have to worry about Covid interrupting my trip—as if the very hairs of my head were numbered by whatever anti-priesthood powers worked to take the trip from possible to probable and even enabled by the universe. All the trip insurance I’d purchased seemed less likely to be required.

I woke the morning of the event with plans to visit the British Museum in the morning and St. Paul’s Cathedral that evening for their annual Britten’s Ceremony of Carols. I still enjoy some religious ritual, particularly in such historic buildings and without any externally or internally-imposed requirement to feel impressed or inspired by the message. The morning of my flight to London, I’d completed the final class of the semester in an audited, history course on Stuart England at the University of Colorado. I’d get to see the famed cathedral while partaking in an annual tradition at St. Paul’s. However, that morning my lumbar spine, as it was wont to do, disagreed with the prospects of standing in a long queue at St. Paul’s. Walking, a reliable method of relief, had proved ineffective due to the repeated stopping and standing required to explore such a massive museum. I retired to my minuscule hotel room early in the afternoon where I debated not going to St. Paul’s since I understood that standing in an exhaustive queue for the event marked the third leg of a stool of surety for which the remaining two legs are death and taxes—I’d surely be in pain that evening for the Merry Hitchmas event. The Lord giveth and the Lord taketh away…

Thus it was that after a nap, some decompression exercises, and a nephilim-sized dose of naproxen, I found relief. I almost reveled in the tube journey and walk in the damp winter cold which, in London to my sensibilities, felt warmer after the sun set. My backpack carried a book/autograph-pad for each of the associated speakers, a bottle of breath freshener spray, and a letter to Richard Dawkins. I arrived forty-five minutes early as did many others. The venue provided a bar in an upstairs map room where we could drink and mingle. I knew no one, thus I neither drank nor mingled. I wish I could have brought myself to do the latter without coming across as the stereotypical, annoying American.

According to the Royal Geographical Society website, their auditorium seats nearly 700 people and it was nearly full during the event. I would later observe that Stephen Fry proved to be the biggest draw for people wanting a book signed. Many of us were there for our appreciation of the legacy of Christopher Hitchens. Message boards leading up to the event featured arm-chair Hitchens experts who knew that Christopher detested the idea of collecting heroes or hero worship. Hitchens did find Christmas intolerable from the incessant music to the politicization and faux outrage of the imaginary war on Christmas. Contrary to their conclusion that the event was antithetical to Hitchens’ character and legacy, I think he’d have appreciated the irony of celebrating his legacy, the day before the anniversary of his death. He’d revel in the idea that the event’s name—Merry Hitchmas—might inflame the scant sensibilities of those in a febrile scavenger hunt to be offended at their pretend victimhood in the war on Christmas. In an effort to raise funds, Atheism UK auctioned off a large painting of Christopher, to be autographed by his four friends, as collectible fan paraphernalia. I do think Hitchens would have been at the very least embarrassed by such an effigy of himself. I suppose if the depiction evoked an appropriate sense of his charm and sexual charisma, he may have found it somewhat amusing.

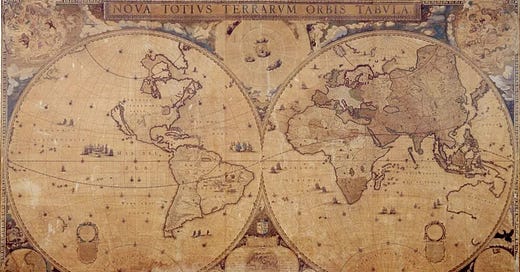

Johness Blaeu double hemisphere map on the walls of the RGS. Note California as an island and the vacant unknown of northwest Canada in 1648.

I am confident that he wouldn’t want us to honor him in some papist fanatic, worshipful fashion. That would be country to his legacy. In that vein the Royal Geographical Society provided an entirely appropriate venue for honoring Christopher’s legacy on the eve of the anniversary of his death. The first map that caught my attention was a world map from the mid 17th century courtesy of Dutch cartographer Johannes Blaeu. In the double-hemisphere map that commemorates peace after the thirty-years war, California is depicted as an island. The marginally explored, 760 mile long peninsula of Baja California is likely to account for this distortion of the west coast of North America. Everything is out of proportion as we know it today, particularly the frontiers of imperial reach. Dutch, French, Spanish, and English cartographers got as much wrong about colonial lands as the politicians did about those civilizations and nations they felt they had the divine right to govern. Cartographers did their best with the limits of their tools, committed to getting things right, they gave a shape of the known world that others could and were expected to improve upon.

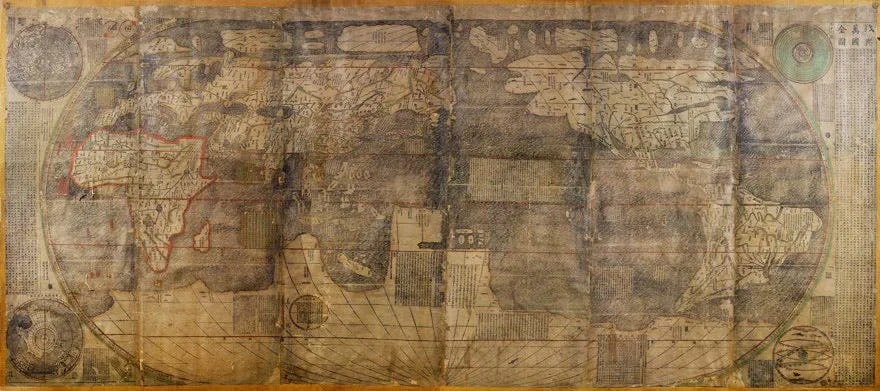

Kunyu Wanguo Quantu map of the world. Reproduced c.1644 from a map made c.1602.

Chinese maps of the world added insight to existing western European sensibilities. Setting satellites into orbit has given us breathtaking views of our home, rendering a lucid understanding of the globe our species has inhabited for over 100,000 years. Despite our growing understanding, we marvel that those who went before us managed to navigate the oceans with compass and sextant and even those who simply followed stars and solar pathways. They drew maps that steered their successors course until we could make them more exact. The regression into flat-eartherism is a warning to those who wish to ignore the legacy of explorers just as the regression into Christian nationalist, monarchist fervor make events like Merry Hitchmas all-the-more important and venues like the RGS doubly venerable. These secular tabernacles committed to historical preservation not merely for its own sake but to remind us that building upon hard won knowledge is a the legacy of all who dare to sail beyond the borders of what is known. The legacy is to persevere into discovering what can be known and challenging those who say we know all there is of value to know on account of desert revelations.

For me, amongst his fathomless wit, boundless knowledge, and strident opinions on the shape of the world, that is the legacy of Christopher Hitchens. He explored the boundaries of knowledge and reason as an explorer journeying into darkest Africa to give us a clearer idea of the shape of our world. Modern journalists, not content to be told how the world is, also help us achieve empathy from those with whom we do not share recent heritage. They show us our similarities where dogmatic entities want us to focus on our differences. They practice what Orwell, one of Hitchens’ many literary influences, said of himself, that not only could he write but, perhaps more importantly, he had a power within himself to face difficult facts with integrity. They wrote with an honesty that was not apologetic toward themselves or their nations chauvinistic sensibilities.

As a writer Hitchens is unmatched in his prolificacy. As a debater, he was unmatched in his reason and rhetoric and in his ability to win any crowd’s amusement and admiration. Douglas Murray said at the event that Hitchens had a remarkable ability to not only impress his readers but to make his readers eager to impress him. I gathered from each speaker, that Christopher possessed another rare capacity that permitted him to be friends to all, appreciating more those who disagreed with him than those prone to sycophancy. His oft repeated axiom its not what you think but how that matters is the essence of exploration and a prerequisite to discovery. If an authority in map-making tells you that California is an island, commitment to reason and reality demands that when confronted with new data or compelling arguments, we be prepared to replace their old map with a newer one. Christopher was an intellectual cartographer, and those of us who learned to admire him, also learned that heroes are dangerous because the idol/idolizer relationship naturally causes us to mistake not merely the map for the place, but the mapmaker for the knowledge-giver. His legacy was not to simply adopt maps from others, though he expressed profound respect for those whose maps informed his own: George Orwell, P.G. Wodehouse, Socrates, Thomas Jefferson, Thomas Paine, and Albert Camus to name but a few. In my estimation, he encapsulated his legacy in his book Letters to a Young Contrarian:

“Beware the irrational, however seductive. Shun the 'transcendent' and all who invite you to subordinate or annihilate yourself. Distrust compassion; prefer dignity for yourself and others. Don't be afraid to be thought arrogant or selfish. Picture all experts as if they were mammals. Never be a spectator of unfairness or stupidity. Seek out argument and disputation for their own sake; the grave will supply plenty of time for silence. Suspect your own motives, and all excuses. Do not live for others any more than you would expect others to live for you.”

I’d absorbed much of his religious debate footage available on YouTube before I looked for his name at the bookstore. One available work published posthumously, Mortality, is a collection of his musings as he submitted to devastating treatments for crippling esophageal cancer. I cringed at Hitchens reciting Auden’s observation, as the poet searched for courage in the despair of September 1, 1939, “All I have is a voice to undo the folded lie…” became to poignant a reminder to Christopher that his powerful oratorical device—(for blasphemy and for insight, often simultaneously)—could be crippled or lost even in his survival.

With that failing voice, he gave a stirring speech at his final public appearance at the end of October 2011. Gaunt of body but still fervent in gaze despite his weary eyes, he persevered. The grim realization of those who watched the speech since December 15, 2011 is that we know Christopher will not speak to us again—not quite his eulogy but feeling like the final words of one whose fate is sealed. He said:

“I guess you will know now that the words of one of my favorite poets, Ernest Dowson, are quite often with me. Thousands stole them, actually, from the Roman poet Horus. ‘I’m not as I was.’ And though, as I know as well as you do, there’s no point in arguing about the actual date or time of departure because I like to think there would be no good time. I hope you agree with that. There would always be something that I urgently felt I would just do or say. And one mustn’t define or give into self-pity about that. But at this present moment, I have to say, I feel very envious of someone who’s young and active and starting out in this argument. Just think of the extraordinary things that are happening to us.” (Emphasis added)

His implied charges in both passages managed to shift the cargo in my hold and in the rebound of trimming sails and rudder, I’ve found that not only do I want to write, like Hitchens said in Letters…, referring to Rainer Rilke’s own Letters to a Young Poet, I write because I must. I made the trip to London because of Christopher’s legacy that awakened me to the compulsion I’d always had and that he elucidated: “If you write, it must be the thing not that you want to do or would like to do; it must be the thing you feel you have to do.” Everyone has a story in them and I’d written several already. What Hitchens made me want to do is to stop writing merely to offer escape and reach into my experience, tapping into honesty in which I hoped my writing would offer insight.

I’d hardly taken my seat when I looked up to see noted YouTube atheist, Alex O’Connor, walking directly toward me. On reflex and with corresponding awkwardness, I called his attention and he graciously spoke to me for a moment and, without a hint of annoyance, submitted to a selfie/ussie. (He repeated this interaction throughout the evening with many others.) With the audacity of a man knowing his end is near I approached Alex after the event and, taking security in the expression that fortune favors the bold, I inquired at his availability and interest in joining me for drinks and discussion at some nearby pub or penny university. He politely declined due to other plans only to turn back to me to say, “Good on you for asking, though.” I did feel he meant it.

Alex remarked that I was going to make him look short so I squatted to bring our physical heights in closer alignment.

Imagine my pleasure when the opportunity to present books for signing arrived and I found that Stephen Fry occupied the attention of so many that it offered me a personal moment with Douglas, Richard, and Lawrence. To Richard, I was able to express my appreciation to the elder statesman and hand him a letter I’d written to him more than four years earlier but had never sent, believing he’d never actually receive it. I still didn’t know if he’d actually have interest in reading it but, to my satisfaction, as I waited to speak with Lawrence, I noted that Richard had already opened the envelope to my moderately sensational attempt at expressing gratitude. He was in the middle of a lull and scrutinized the verbose letter.

The tri-folded pages to Mr. Dawkins’ left constitute the thank youletter I gave him.

Lawrence remembered me in part because we’d established contact prior to the Boulder event and maintained it since then. I felt honored that he responded to a personal query. He indicated he was happy that I’d made the trip and signed in my book, The Edge of Knowledge: “Great to see you again in London. Next time, who knows?” In my distracted excitement and remembering I’d taken photos with Lawrence at the Boulder, Colorado event, I failed to obtain a photo with him! (Afterward, upon scouring my phone and my friend’s, neither of us could find a photo though we both remember taking one.) His insinuation of meeting again at a future event is an opportunity. I’ll have to say that more than the photos, the warm welcome, good humor, and friendliness of Mr. Krauss meant and continue to mean a great deal to me.

Douglas entertained me twice that evening and, contrary to what I expected, he was by far the most engaging of the four. I shouldn’t be surprised, for in the reminiscences they each shared of Christopher, Douglas spoke of the sincere interest Christopher took in both himself and other budding writers. Regardless of my commitment to avoid making heroes of them, I couldn’t help but think of another Auden line: “Looking up at the stars I know quite well that for all they care I can go to hell.” Douglas did not give the impression of a star either annoyed or inured by plebeian admiration. On the contrary, just a few months my senior, proved gregarious. He asked me “What do you do?” I answered sincerely, “I’m a dentist, but I was supposed to be a writer.”

His expression brightened as paused in his cursory signing of my book and raised his eyes to meet mine. He seemed genuinely surprised and interested so I haltingly referred to the above quotes of Christopher that motivated me and expressed that I was “trying to find my audience.”

Douglas encouraged me to continue writing, signed my book, and bid me good evening. I reentered the extensive queue to meet Stephen Fry. As I waited, I made conversation with a living soul for the second time since I’d arrived in London. A couple beside me commented on the sorry state of the world in the wake of the U.S. presidential election. I took occasion to agree with them. They asked and I confirmed that I was indeed from the states. Colorado in fact. They proved friendly, gregarious, and remarked that I was the only yankee other than Lawrence Krauss that they’d seen—or rather heard—at the event.

The line moved me away from them. When I reached Stephen, I asked him to sign his book of retold Greek myths to my daughter who also shares his love for mythology. I amused him by recounting that I owed to him my interest in etymology. (If you haven’t heard Stephen Fry explain from where we acquired a word, you may be missing out.) My intention was to amuse him, thus, I said with all honesty, “but initially because of the word ‘troglodyte’ that you said in the movie I.Q.” He did give me a hearty, belly laugh and posed for a picture.

Stephen Fry reposing when the previous photo was blurry. (It does show his amusement at my joke as well as my own shameful amusement at myself.)

When I noted that Douglas’ queue held only one other person and that the event was winding down, I realized I may have another chance to approach one of the “stars that do not give a damn.” The woman ahead of me had no book but told me that Douglas Murray and Stephen Fry are her favorite people in the world. I agreed to take her picture with Douglas and she offered to return the favor. Douglas recognized me on my return, and I asked if he’d indulge a question. He showed no irritation. Quite the contrary, he embodied the opposite of Auden’s earthly “indifference” humans must least of all dread from others. At my inquiry, he generously gave me advice writing and how to choose what is worth my effort to write about. I starkly disagree with Mr. Murray on major political points but I have no doubt conversation over coffee or cocktails would prove stimulating and insightful. Time will tell if I follow his advice. For now, I’m grateful he so graciously took the time to offer it.

Douglas Murray. I’m ashamed to say that I did not think he would be approachable and gregarious. He turned out to be a simple example that contradicted the axiom, “never meet your heroes.” (Don’t collect heroes anyway.)

I regrouped with my photo taker who wanted to get in line with Stephen Fry, but the line had disappeared and he was preparing to leave. “Oh he’s very kind,” I told her. She expressed embarrassment at approaching him and I volunteered to be an audacious American for her. Had he not been on a long phone call at the time, I might have tried. Our association proved to be one of many highlights of the evening. We were headed to the same tube station which offered us time to talk about what brought us to the event, our children, and what Hitchens books I would recommend to her as she was unfamiliar with his work. I recommended, in order, Letters to a Young Contrarian, his biography Hitch 22, and God is Not Great.

The simple interaction reinforced the legacy of Christopher that brought Dawkins, Murray, Fry, and Krauss together during the yuletide season to ironically honor their mutual but not at all common friend. It brought an audacious American across the pond to join the simple evening of reminiscence. Hitchens star burns brightly, producing heat giving light to the words and insights of those who venture unfamiliar frontiers in his footsteps. We who embark, taking up his charge to “never be a spectator of injustice or stupidity” admire the path he trod that ironically invites us to make our own.